Wake up, work, sleep, repeat. Was this what I really wanted? I’d been existing in an environment where nothing was ever good enough, where there was a constant need for more, and it suddenly felt so empty.

Realizing how blessed I have been my whole life, I wondered what I was actually giving back. And that’s when it hit me. Instead of just striving for a bigger career, in an ungrateful environment, it was time to contribute to something greater. It was time to give meaning to my life. It was time to start thinking how I could not only bring satisfaction to my own life, but also to that of others. It was time to pay it forward.

I decided to look at volunteering options. Working with children was the first thing that came to mind, finding a way to help them build towards a better future. As a result, my trip to Peru was the first to take shape. It then became more difficult. What else could I do? The whole point was to figure out what would work for me, as I wanted to make this a permanent fixture in my life. It’s not just about donating money, it’s also about physically contributing, taking the time to contribute, and being hands-on. When an acquaintance suggested I do something connected to diving, because diving and the ocean are my passion, I knew this was something I had to explore. After doing some thorough research, I decided to join Operation Wallacea, known as Opwall.

Opwall is an organization that operates a series of biological and conservation management research programs in remote locations across the world. These expeditions are designed with specific wildlife conservation aims in mind—from identifying areas that need protection, through to implementing and assessing conservation management programs. I decided to volunteer at their marine-based research expedition in Akumal, Mexico as a Research Assistant. And what an experience that was! Apart from taking me back to basics, it taught me so much about how we are killing our oceans! I had been so blind until the day I joined Opwall; this experience was a real eye-opener.

But let me start at the very beginning of the expedition. Before I arrived in Akumal, I didn’t really know what to expect. As I’d joined the marine-based research expedition, I thought I’d be sleeping at a beachfront residence. I couldn’t have been more wrong. The bus from Cancun dropped us at the side of the road, where we then had to transfer our luggage into cars so that we could reach our accommodation, which was in the middle of nowhere. Yes, indeed, no nice beachfront villa, but welcome to the jungle! There I was, scared of anything that crawls, in the middle of a jungle with snakes, scorpions, spiders, and a whole lot more! Having a scorpion visit us in our room on the first night was terrifying and I had to get over my fears quickly.

Moving on to the sleeping arrangements… I was sharing a dorm, something I hadn’t done in over 20 years! I am a very private person, so this was another challenge. I have to say that I was very lucky to share a dorm with very lovely ladies. There was a lot of respect and appreciation between us all which made it easier. I struggled more with the air-conditioning rule: it was turned on from 8.30 pm until 5.30 am. Not being able to control the air-conditioner was something that I didn’t particularly like. And the same with the cold showers! How I enjoyed my first hot shower after the expedition! I never knew one could get so much pleasure out of something we so take for granted. We did have a pool, though, surrounded by hammocks (one of my favorite places to read). But I never figured out how on earth it was possible to get so many mosquito bites on my buttocks, so reading time in the hammock soon came to an end.

What I learned from all that is, as a city girl, I adapted to the whole situation in the blink of an eye. I was there for a purpose and I just settled in.

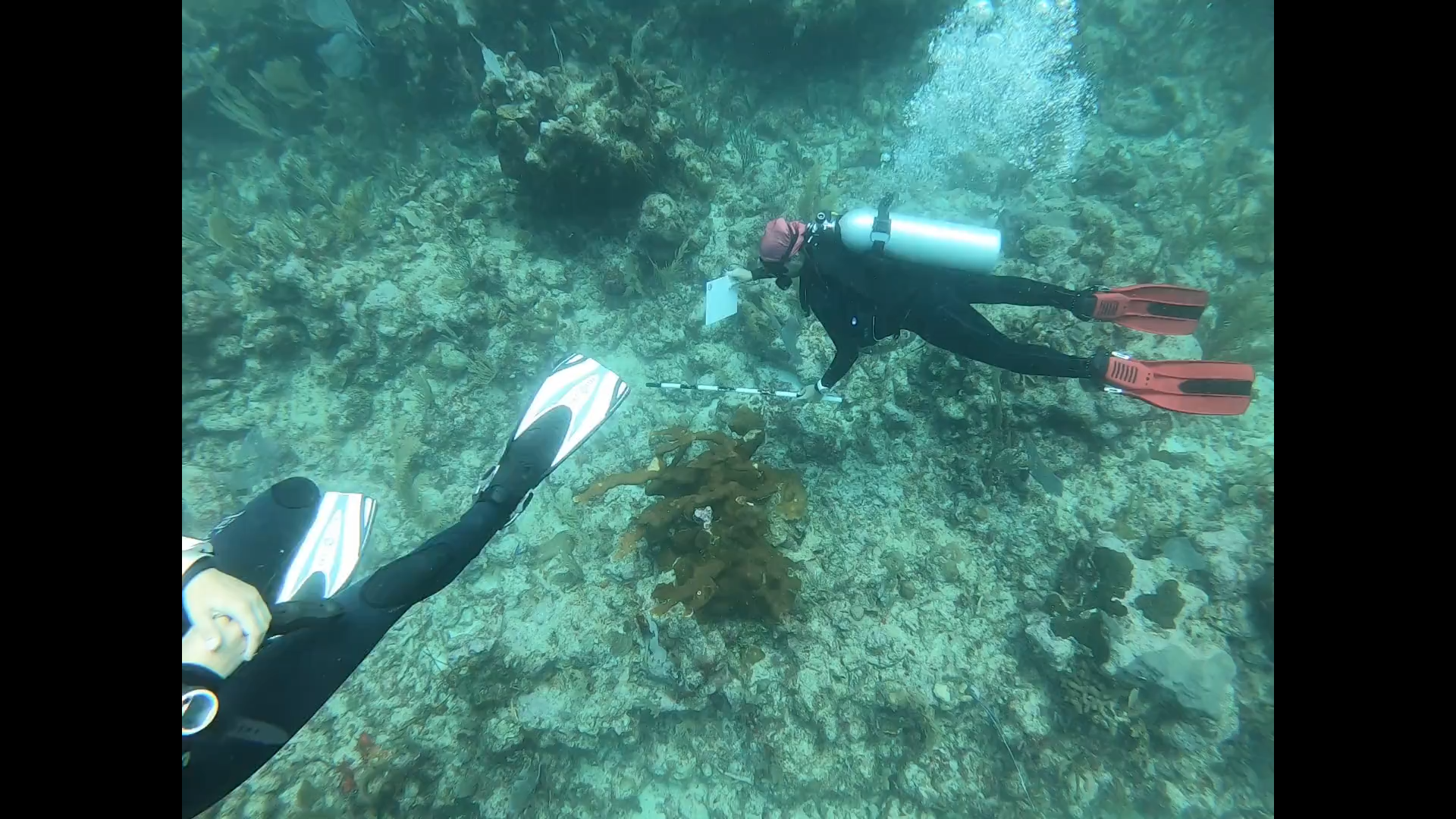

After being put on an intensive Coral Reef Ecology Course, I was ready to collect as much data as possible. As a Research Assistant and advanced diver, my main responsibility was to collect coral data through coral mapping (shown in the above pictures). It was important for me to know the most important corals so I could spot them and look for healthy ones that were at least half a meter long. Once found, I measured their length, width, height, and depth and decided on mortality %. The time taken from getting into the water to the location of the coral also had to be recorded, as well as the coral code and type. Once back from the dive, I would do the data entry.

Everything during the trip was timed to precision: 6 am breakfast , 7 am pick up by the van, 7.30 am dive (coral mapping), 10 am data analysis, 11 am lunch, 12 pm dive (coral mapping), 1 pm data entry, 3 pm snorkel transect, 5 pm transfer to base, and 6.30 pm dinner. After either a short course or presentation after dinner, I’d be in bed by 8 pm!

What exactly was the aim of the expedition? It was all to do with coral, an animal that has survived on this planet for more than 200 million years and is now in extreme danger. More than 500 million people depend on healthy coral reefs for food and millions more rely on thriving reefs to drive their tourism-based economies. Coral reefs protect coastal communities by creating natural sea walls that dramatically diffuse wave energy and storm surges. They also serve as underwater rainforests, regulating atmospheric gases. They provide medicinal benefits for humans and are home to a quarter of all marine life. However, in the last 30 years, half of the world’s coral reefs have been lost. Unprecedented bleaching, a stress response that leaves corals vulnerable to massive die-offs, has devastated reefs. A warmer planet increases the frequency of bleaching events, which reduces the time corals have to recover from the previous bleaching and increases their chances of dying. But the corals and their internal algae do more than just help each other survive. They also suck down carbon dioxide from the atmosphere—reducing the severity of climate-change effects—and generate oxygen. Bleaching occurs when corals are stressed by too-warm or too-cool waters, a more acidic ocean, or local factors such as sediment and polluted runoff. As a result, the corals expel the algae living inside them, leaving their bony skeletons a translucent white.

So, in a race against time, researchers have been experimenting with breeding “super coral” to counter the effects of climate change on the world’s reefs. You may know that corals reproduce sexually. All individual corals spawn on the same night of the year. Before spawning, the gamete bundles sit at the polyp opening, ready to be released. The “setting,” but also the hungry invertebrates on and around the colonies, indicate that the coral will likely spawn soon. Like us, they await the release of gamete bundles during mass spawning events. Each year, Caribbean corals reproduce during a mass spawning event timed by the summer full moon. The team monitors their spawn, collects gametes, and conducts fertilization. In this way, we support the reproduction of corals and help save the ocean!

To be continued…

#conservationofthecean #savetheocean #coralmapping #volunteer #operationwallacea #reuse #reduce #recycle

Terms & Conditions. © 2023 by V R B Management Consulting Co. LLC